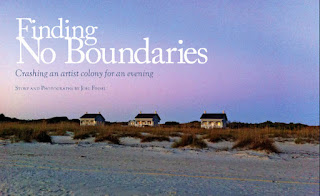

Finding No Boundaries: crashing an artist colony for an evening

Finding No Boundaries

crashing an artist colony for an evening

SALT Magazine

October 2014

Words and Photos by Joel Finsel

At the eastern tip of the Cape Fear Coast, where the northern and southern currents collide, the surf forms sideways rather than parallel to the shore — the waves project outward from the beach in a line that almost seems palpable, as if you could walk along it, like a path. Some people think this point gave the Cape Fear its name, since so many ships would wreck on the sandbar there.

I had come to Bald Head Island to learn about No Boundaries, an international artists’ colony, but was lost. The tram driver had taken me to the wrong house, leaving me alone on a stranger's porch just before dark. I rang the bell and a disheveled man came to peer at me from behind the glass.

“Hello,” I said, “are you the chef?”

He looked at me with raised eyebrows.

Somewhat desperate, I held up my Moleskine as credentials. “I’m a journalist covering the artist colony,” I explained. “I'm sorry, I was told I’d be staying with the chef.”

Something in my eyes must have let him know I was something other than the horror-story villain who shows up at your vacation house in the off-season just after you and your wife have settled in for the evening. Or possibly he was just bored and looking for a touch of adventure. He drove me to the old lighthouse keepers’ cottages, where the artists stayed. Someone there would know where to put the outsiders like me.

Many artist colonies are like utopian experiments where creatives live and interact with one another. Those not invited tend to shrug them off as a bunch of lucky people able to escape the status quo for some time in paradise while the rest of us continue to suffer. But the story of No Boundaries is more daring than that. It began in 1993 when a Wilmington painter named Pam Toll traveled to an artist colony in Macedonia. The country had just been formed two years before. Toll had a friend who’d studied there and come back full of stories about the fresh enthusiasm surrounding the arts. Macedonia had thirteen arts colonies, the woman said. Toll applied, and months later found herself at an 800-year-old monastery in the Osogovo mountains, about seven miles from today’s Bulgarian border.

Living among the Macedonian people, Toll says, she felt as if she had been removed from time. Men walked their goats into town. She discovered that a hike through the hills meant multiple invitations to sit and sip rakija, a brandy made from a variety of native herbs and fruit. She left with an impression of having been initiated into an international tribe of artists, many from countries still at war with each other –– Serbia, Kosovo, Albania. If they could live together and inspire each other, then peace seemed possible.

Toll was twice asked to return to the Osogovo colony in subsequent years, and to bring another American artist with her. She first invited Gayle Tustin, a painter friend from Wilmington. “Pam and I were in a painting group together before she went on the first trip,” Tustin says, “and I saw a huge change in her when she came back.” The next year Toll brought along local painter Dick Roberts, a co-founder of Acme Arts Studios. Afterward, in talking, the three painters realized that the experience in Macedonia had profoundly affected each of their lives. It was then, in the mid-nineties, that they started dreaming up the concept of No Boundaries.

The question became, location — where to place their particular thumbtack on a world map of similar enclaves. Nearby, picturesque, and relatively undeveloped, Bald Head Island already offered retreats for solo artists (Toll had been awarded one there too). And she knew the president of island’s management company, Kent Mitchell, from swimming at the YMCA.

Mitchell happens to be an architect with a drawing habit. They struck a deal. Bald Head would transport the artists to the old lighthouse keeper’s station and give them accommodation in the three cottages there. In return each artist would leave behind one painting per week of their residency.

Toll, Tustin, and Roberts met weekly for a year to manage the details. “We knew we were never going to make money,” Tustin said. “We considered it to be one drop in the sea for world peace.” Sixteen years later, painters from all over the world have done stays at No Boundaries. If every artist’s journey to the colony were represented by a different colored thread on the map, the end design would be a multi-layered tapestry.

Last year marked a turning point in the history of the colony. The founders — Toll, Tustin, and Roberts — stepped down, and a new president, Michelle Connolly, took over. Connolly is a Wilmington artist with roots in both England and Australia, the perfect No Boundaries blend of international and local. With the change in leadership, the format has changed a little, too. The colony now invites international artists every year, rather than on alternating ones. But the founding spirit remains: “There are literally no boundaries,” Connolly said.“It’s funny how often we repeat the saying, but it’s true.”

I thought of one. “What about the rest of the community?” I asked. “Are there boundaries against people visiting who aren’t a part of the colony?”

“We encourage the public to come,” she said, “especially during the open-studio day. Visitors are welcome other times, but there’s no guarantee the artists won’t be out painting in the marshes. It takes some doing to get there, but that’s not because they are trying to keep people out. In fact, we invited an entire class from DREAMS [Center for Arts Education in Wilmington] to come out last year and spend the day with the artists.”

When I posed the same question to Tustin, she said, “No Boundaries is remote on purpose, but more to give the artists space to make breakthroughs than to keep other people away.”

The artists arrive to find the floors of the three modest houses of Captain Charlie’s Station covered with plastic, to keep the paint off the floor. The structures take their name from lighthouse keeper Charles Swan, whose family and staff occupied the government-issue buildings between 1903 and 1933, back when supplies had to be air-lifted in by planes landing on the beach at low tide. The entire layout looks to be about the size of one of the neighboring mansions visible from the beach.

Each artist stakes out his or her own place to work and sleep. They live communally for two weeks. Dinner is provided, but for most of the rest of the time they are on their own. It’s a fascinating Petri dish to observe. When I was there, applicants had come from as far away as Indonesia, Australia, and Rwanda. Styles ranged from primitive and outsider, to figurative and abstract. The close quarters force exchanges, resulting in a cultural cross-pollination. As someone crashing the party midway, I felt a little like I was walking onto the set of a reality show in the middle of the season without having watched a single episode.

The first artist I met was Brandon Guthrie, who welcomed me onto the porch with a smile. He offered me a beer, and we sat down on rocking chairs to stare at the moon’s reflection melting into the sea. Guthrie said that before coming to the island he’d felt burnt out, artistically. He’d been making a lot of similar work for weeks on end. He had also recently become chair of the Humanities and Fine Arts Department at Cape Fear Community College. He welcomed the added responsibilities but said it was “nice to set them aside a while.

“Something about coming out here,” he said, “it’s like opening up all the windows in your body and letting fresh air in.”

Guthrie described how strange it felt to be around so many people who liked to talk about abstract ideas as if they were normal topics of conversation. “We tend to hold back from those types of discussions in ordinary life,” he said. “Out here, it’s the kind of medicine people need. It’s important work, definitely not a vacation.”

Inside the cottage, a group of five or six other artists were passing around a book of Leonard Cohen’s poetry and taking turns reading poems out loud. After listening for a few minutes I decided to walk into the kitchen and say hello to the chef, who was supposed to be my roommate. To my surprise, he turned out to be a friend I’d known for years (Jameson Chavez, the head cook at Manna, where I tend bar). Having watched him cook a hundred times, I could tell by the way he smashed the butternut squash that something was different about him. He was taking his time.

As the artist assigned to be his kitchen helper poured us each a glass of wine, I asked the chef what was up. He responded that this was his first day off in weeks. When he’d woken up that morning knowing he would have to travel all the way here to cook for a group of strangers, he hadn’t felt particularly motivated to get out of bed. He had heard about No Boundaries, and knew that the colony had a tradition of inviting in chefs to cook for the artists, but he hadn’t really known what to expect, and confessed that he’d almost bailed. “But all of my gloom lifted when I arrived,” he said, smiling. “Everyone has been so friendly. I haven’t felt this calm in a long time.”

He had been warned to prepare for having little in the way of cooking tools or spices, so he decided to keep the menu simple: roasted pork tenderloin with braised cabbage. Happy to discover a blender, he puréed red chile, onion, garlic, and vegetable stock into a sauce as the rest of the artists began to arrive.

I asked the first, a painter named Jonathan Summit, about his experience so far.

“It’s a gift from God,” he said, sitting down next to me. “I feel like I could go anywhere in the world and know someone who is a No Boundaries alum.”

Others began trickling in. Soon there were about twenty of us seated around a couple of long tables. Every time my glass of wine got dangerously close to empty, someone topped it off. After Jameson had stood and explained the menu, the rest of us cheered and clapped. I recorded over two hours of dinner conversation, but when I replayed the files, there was too much chatter, interrupted by toasts and spontaneous laughter, to render them indecipherable. But I know it was an excellent night.

There was a Rwandan artist, Nkurunziza Innocent, whose colorful abstract canvases and shell-totems I had seen. There was a Chinese tea master named Weihong, who had brought with her, to that remote Atlantic outpost, teacups salvaged from a shipwreck in the Pacific. Wilmington’s own Harry Taylor was there, making his distinctive tintype photographs. An Indonesian artist named Jumaadi, who had a show scheduled in Charleston right after the colony closed, played the guitar and sang. It was well past midnight when the chef and I finally staggered off to our house a half-mile away.

Since its inception, No Boundaries has existed mainly for painters, but under Michelle Connolly’s leadership the roster has expanded to include more film-makers and photographers, as well as the occasional writer. The outlier slot for this fall’s class will go to a singer-songwriter from Nashville named Gabriel Kelley (it’s not clear yet what he will leave behind, in place of two paintings — a song?). The group arriving on Bald Head in November will include artists from Brazil, Spain, Argentina, and Cuba (pending visa approval).

For anyone interested in a casual visit, Open Studio Day is Tuesday, November 18, from 2–5 p.m., at Captain Charlie’s Station. Those unable to make the trek — including but not limited to those who have heard about ‘Cloden,’ the ghostly child bride said to inhabit the middle cottage — there will be an exhibition in Wilmington. The Wilma Daniels Gallery at Cape Fear Community College will open the show with a reception on November 22. Interested buyers, or anyone with an interest in art, will have a rare chance to see pieces from all over the world, made right here on our coast during two intense and transformative weeks.

Joel Finsel profiled humanitarian inventor Jock Brandis in our March issue.

crashing an artist colony for an evening

SALT Magazine

October 2014

Words and Photos by Joel Finsel

At the eastern tip of the Cape Fear Coast, where the northern and southern currents collide, the surf forms sideways rather than parallel to the shore — the waves project outward from the beach in a line that almost seems palpable, as if you could walk along it, like a path. Some people think this point gave the Cape Fear its name, since so many ships would wreck on the sandbar there.

I had come to Bald Head Island to learn about No Boundaries, an international artists’ colony, but was lost. The tram driver had taken me to the wrong house, leaving me alone on a stranger's porch just before dark. I rang the bell and a disheveled man came to peer at me from behind the glass.

“Hello,” I said, “are you the chef?”

He looked at me with raised eyebrows.

Somewhat desperate, I held up my Moleskine as credentials. “I’m a journalist covering the artist colony,” I explained. “I'm sorry, I was told I’d be staying with the chef.”

Something in my eyes must have let him know I was something other than the horror-story villain who shows up at your vacation house in the off-season just after you and your wife have settled in for the evening. Or possibly he was just bored and looking for a touch of adventure. He drove me to the old lighthouse keepers’ cottages, where the artists stayed. Someone there would know where to put the outsiders like me.

Many artist colonies are like utopian experiments where creatives live and interact with one another. Those not invited tend to shrug them off as a bunch of lucky people able to escape the status quo for some time in paradise while the rest of us continue to suffer. But the story of No Boundaries is more daring than that. It began in 1993 when a Wilmington painter named Pam Toll traveled to an artist colony in Macedonia. The country had just been formed two years before. Toll had a friend who’d studied there and come back full of stories about the fresh enthusiasm surrounding the arts. Macedonia had thirteen arts colonies, the woman said. Toll applied, and months later found herself at an 800-year-old monastery in the Osogovo mountains, about seven miles from today’s Bulgarian border.

Living among the Macedonian people, Toll says, she felt as if she had been removed from time. Men walked their goats into town. She discovered that a hike through the hills meant multiple invitations to sit and sip rakija, a brandy made from a variety of native herbs and fruit. She left with an impression of having been initiated into an international tribe of artists, many from countries still at war with each other –– Serbia, Kosovo, Albania. If they could live together and inspire each other, then peace seemed possible.

Toll was twice asked to return to the Osogovo colony in subsequent years, and to bring another American artist with her. She first invited Gayle Tustin, a painter friend from Wilmington. “Pam and I were in a painting group together before she went on the first trip,” Tustin says, “and I saw a huge change in her when she came back.” The next year Toll brought along local painter Dick Roberts, a co-founder of Acme Arts Studios. Afterward, in talking, the three painters realized that the experience in Macedonia had profoundly affected each of their lives. It was then, in the mid-nineties, that they started dreaming up the concept of No Boundaries.

The question became, location — where to place their particular thumbtack on a world map of similar enclaves. Nearby, picturesque, and relatively undeveloped, Bald Head Island already offered retreats for solo artists (Toll had been awarded one there too). And she knew the president of island’s management company, Kent Mitchell, from swimming at the YMCA.

Mitchell happens to be an architect with a drawing habit. They struck a deal. Bald Head would transport the artists to the old lighthouse keeper’s station and give them accommodation in the three cottages there. In return each artist would leave behind one painting per week of their residency.

Toll, Tustin, and Roberts met weekly for a year to manage the details. “We knew we were never going to make money,” Tustin said. “We considered it to be one drop in the sea for world peace.” Sixteen years later, painters from all over the world have done stays at No Boundaries. If every artist’s journey to the colony were represented by a different colored thread on the map, the end design would be a multi-layered tapestry.

Last year marked a turning point in the history of the colony. The founders — Toll, Tustin, and Roberts — stepped down, and a new president, Michelle Connolly, took over. Connolly is a Wilmington artist with roots in both England and Australia, the perfect No Boundaries blend of international and local. With the change in leadership, the format has changed a little, too. The colony now invites international artists every year, rather than on alternating ones. But the founding spirit remains: “There are literally no boundaries,” Connolly said.“It’s funny how often we repeat the saying, but it’s true.”

I thought of one. “What about the rest of the community?” I asked. “Are there boundaries against people visiting who aren’t a part of the colony?”

“We encourage the public to come,” she said, “especially during the open-studio day. Visitors are welcome other times, but there’s no guarantee the artists won’t be out painting in the marshes. It takes some doing to get there, but that’s not because they are trying to keep people out. In fact, we invited an entire class from DREAMS [Center for Arts Education in Wilmington] to come out last year and spend the day with the artists.”

When I posed the same question to Tustin, she said, “No Boundaries is remote on purpose, but more to give the artists space to make breakthroughs than to keep other people away.”

The artists arrive to find the floors of the three modest houses of Captain Charlie’s Station covered with plastic, to keep the paint off the floor. The structures take their name from lighthouse keeper Charles Swan, whose family and staff occupied the government-issue buildings between 1903 and 1933, back when supplies had to be air-lifted in by planes landing on the beach at low tide. The entire layout looks to be about the size of one of the neighboring mansions visible from the beach.

Each artist stakes out his or her own place to work and sleep. They live communally for two weeks. Dinner is provided, but for most of the rest of the time they are on their own. It’s a fascinating Petri dish to observe. When I was there, applicants had come from as far away as Indonesia, Australia, and Rwanda. Styles ranged from primitive and outsider, to figurative and abstract. The close quarters force exchanges, resulting in a cultural cross-pollination. As someone crashing the party midway, I felt a little like I was walking onto the set of a reality show in the middle of the season without having watched a single episode.

The first artist I met was Brandon Guthrie, who welcomed me onto the porch with a smile. He offered me a beer, and we sat down on rocking chairs to stare at the moon’s reflection melting into the sea. Guthrie said that before coming to the island he’d felt burnt out, artistically. He’d been making a lot of similar work for weeks on end. He had also recently become chair of the Humanities and Fine Arts Department at Cape Fear Community College. He welcomed the added responsibilities but said it was “nice to set them aside a while.

“Something about coming out here,” he said, “it’s like opening up all the windows in your body and letting fresh air in.”

Guthrie described how strange it felt to be around so many people who liked to talk about abstract ideas as if they were normal topics of conversation. “We tend to hold back from those types of discussions in ordinary life,” he said. “Out here, it’s the kind of medicine people need. It’s important work, definitely not a vacation.”

Inside the cottage, a group of five or six other artists were passing around a book of Leonard Cohen’s poetry and taking turns reading poems out loud. After listening for a few minutes I decided to walk into the kitchen and say hello to the chef, who was supposed to be my roommate. To my surprise, he turned out to be a friend I’d known for years (Jameson Chavez, the head cook at Manna, where I tend bar). Having watched him cook a hundred times, I could tell by the way he smashed the butternut squash that something was different about him. He was taking his time.

As the artist assigned to be his kitchen helper poured us each a glass of wine, I asked the chef what was up. He responded that this was his first day off in weeks. When he’d woken up that morning knowing he would have to travel all the way here to cook for a group of strangers, he hadn’t felt particularly motivated to get out of bed. He had heard about No Boundaries, and knew that the colony had a tradition of inviting in chefs to cook for the artists, but he hadn’t really known what to expect, and confessed that he’d almost bailed. “But all of my gloom lifted when I arrived,” he said, smiling. “Everyone has been so friendly. I haven’t felt this calm in a long time.”

He had been warned to prepare for having little in the way of cooking tools or spices, so he decided to keep the menu simple: roasted pork tenderloin with braised cabbage. Happy to discover a blender, he puréed red chile, onion, garlic, and vegetable stock into a sauce as the rest of the artists began to arrive.

I asked the first, a painter named Jonathan Summit, about his experience so far.

“It’s a gift from God,” he said, sitting down next to me. “I feel like I could go anywhere in the world and know someone who is a No Boundaries alum.”

Others began trickling in. Soon there were about twenty of us seated around a couple of long tables. Every time my glass of wine got dangerously close to empty, someone topped it off. After Jameson had stood and explained the menu, the rest of us cheered and clapped. I recorded over two hours of dinner conversation, but when I replayed the files, there was too much chatter, interrupted by toasts and spontaneous laughter, to render them indecipherable. But I know it was an excellent night.

There was a Rwandan artist, Nkurunziza Innocent, whose colorful abstract canvases and shell-totems I had seen. There was a Chinese tea master named Weihong, who had brought with her, to that remote Atlantic outpost, teacups salvaged from a shipwreck in the Pacific. Wilmington’s own Harry Taylor was there, making his distinctive tintype photographs. An Indonesian artist named Jumaadi, who had a show scheduled in Charleston right after the colony closed, played the guitar and sang. It was well past midnight when the chef and I finally staggered off to our house a half-mile away.

Since its inception, No Boundaries has existed mainly for painters, but under Michelle Connolly’s leadership the roster has expanded to include more film-makers and photographers, as well as the occasional writer. The outlier slot for this fall’s class will go to a singer-songwriter from Nashville named Gabriel Kelley (it’s not clear yet what he will leave behind, in place of two paintings — a song?). The group arriving on Bald Head in November will include artists from Brazil, Spain, Argentina, and Cuba (pending visa approval).

For anyone interested in a casual visit, Open Studio Day is Tuesday, November 18, from 2–5 p.m., at Captain Charlie’s Station. Those unable to make the trek — including but not limited to those who have heard about ‘Cloden,’ the ghostly child bride said to inhabit the middle cottage — there will be an exhibition in Wilmington. The Wilma Daniels Gallery at Cape Fear Community College will open the show with a reception on November 22. Interested buyers, or anyone with an interest in art, will have a rare chance to see pieces from all over the world, made right here on our coast during two intense and transformative weeks.

Joel Finsel profiled humanitarian inventor Jock Brandis in our March issue.